So here at last was The Yard, where an expanse of grass sprawled between a small beach house and a quonset hut to our right, reaching inland roughly 20 yards and defining one side of the property. The remaining 30 feet of that line was bisected by the short dirt drive we now dropped into from a narrow dirt road.

On our left, between the car and the beach house, was the legendary volleyball court where the boys – sober, drunk or stoned – hosted beach volleyball sessions that lasted for the better part of every Saturday and some Sundays.

Beyond the sunken posts and net and groomed sand of the volleyball court was Dungca's Beach, from which Alupang Island was about a 10-minute swim across the cove if tide and currents were in your favor. Alupang seemed small from here; you could have draped half a football field over it if that field had been able to take on the shape of a very large coral head.

On the far side of Alupang was Rick's Reef.

"Sweet spot," I said softly, thinking of the last time we'd surfed together. I was home for the summer after my first year of college.

"Are you kidding me? Are you kidding me?" my brother raged, jabbing at my ribs. He'd tried to hide his own enthusiasm, but now all restraint was gone.

A weight had been lifted from all our shoulders with the end of the war. The bombs were no longer shipped to Guam's naval port, no longer trucked to the far northern tip of the island and loaded on B-52 Stratofortresses flying dawn sorties from Andersen to North and South Vietnam. The draft ended the year we were 17 and 16, respectively. Saigon fell to the Viet Cong two years later in 1975.

For all our high school years we'd watched the bomb-laden trucks fly by our bus stop on Marine Drive north of Tumon Bay. Our grade-school friends back in West Virginia became adults in a more peaceful world, though their older brothers might be called to serve in the very same war.

The war was not so distant for us. Sometimes it was unexpectedly personal.

There were the drugs, for one thing, trafficked all the way from the battlefield to the home front to supply a seemingly endless parade of soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines who marched out of high school or college into a world of pain. Some of the pain and some of the drugs spilled over into the civilian world in places like Guam, rest and recreation destinations for the men and women on leave.

Our brother Chet, a year and three months younger than Michael, lost his best friend to a heroin overdose at age 14 under circumstances the police called "suspicious."

You can never be certain about these things, but we were pretty sure this kid was clean. The police found nothing to prove otherwise. We had our own suspicions about boys who may have held a minor grudge; we knew better than to share our suspicions.

That whole crazy time scared us all, and our mother more than anyone was torn about what to do. In the end she thought it best to send Chet to live with our dad in Texas, a decision she'd always question and ultimately regret. This changed our family dynamic forever.

If Michael and I were Larry and Moe, Chet was Curly. We missed him, and we didn't talk about it. We should have talked about it.

Jimmy Carter was president, and the war was truly done in Vietnam as a bunch of radical Islamists held the entire U.S. embassy hostage in Iran. It looked like that might be Jimmy's undoing, and a B-movie actor was making a bid to take his place in Washington. I was a sophomore journalism major at Marshall University, and for the moment all that was distant white noise to me.

"Check out my crib," said brother Miguet, pointing us around the side of the quonset. "Go easy on the grass, nai. We don' drife on it if we don' haff to."

In those days we both slipped easily in and out of an exaggerated Chamoru accent, a nod to our genuine respect for the island's language and culture. We knew we sounded silly, being haoles, so usually it was a lighthearted word or two, sometimes a taste of the kind of wordplay the locals loved.

As locals ourselves for now, we loved it too. But — well, if a native speaker's wordplay was truly brilliant and sometimes hilarious, mine (and probably Michael's, too) might be judged as pale imitation. I wince when I recall the way I mimicked that sing-song accent when we arrived in Guam more than 12 years earlier. It's music to me now, and somehow decades later I'm proud there's a renewed interest in preserving the language, culture and traditions of a place the original inhabitants called Guahan (we have) to affirm that the island's resources were enough to sustain everyone, even those who would come and try to "conquer" the place.

"Laña si Miguet, your flowers are all pasado," I teased. Then followed five minutes of me laughingly shaming him for his bad housekeeping.

The hanging flowerpots on the front porch, lovingly selected and cared for by his girlfriend Dawn, hadn't been touched since she'd left him – again – a few months before. The ashtrays in the otherwise tidy living room were nearly full. Breakfast dishes in the sink hadn't even been rinsed off. The only art on the wall, an album cover of Jimi Hendrix' "Axis: Bold as Love," was hung a little cockeyed.

My critique ended when I saw the shrine, though.

At the very center of this humble dwelling of a boy just making his way in the world for the first time, at the exact intersection of the little living room, the tiny kitchen and the narrow entryway that divided them, just where an open doorway led back to a simple bed and bath, there was a shelf. And on that shelf was a pristine arrangement that expressed the essence of our shared material existence in loving homage to the Buddha.

From about my sixteenth year – the second year after we arrived in Guam – I read everything I could find about the life of the Gautama Buddha, the evolution of his teachings into branches of purist and populist philosophy, and especially Ch'an buddhism which would eventually find its way to Japan as zen buddhism. My brother absorbed a lot of that just by being around me; he read a lot, too.

When our senior class arranged a trip to Japan, I worked all that year at JJ's Ice Cream Parlor in Tamuning so I could save money and fly away for a week with friends and teachers to visit a place about which many of us in Guam had mixed feelings.

Walking Guam's beaches, especially along the island's west coast, you couldn't miss seeing an occasional bunker from which the emperor's army had defended Guam's recapture by U.S. forces. Japan's wartime leaders had commandeered a copra plantation on Rota, just 40 miles north of Guam. Tinian, a little north of Rota, was the point of departure for Little Boy and Fat Man, the atom bombs delivered to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And even farther north in Saipan, Japanese occupying forces opted for mass suicide to avoid capture by the returning Americans.

The Japanese of that generation had taken whatever they wanted wherever they went, and the good people of Guam were not spared. Survivors of those horrors still lived in Guam, and some of them still shared these stories within their families.

Whatever reservations we teenage tourists may have had, Tokyo was amazing. Mr. Wellborn, who taught Japanese at JFK High School, took a few of us with him to visit a zen monastery where he'd lived and studied. As a couple of monks there greeted him warmly and chatted quietly in a language I could not quite follow, I basked in the simplicity of monastic life in a walled garden near the center of the world's most populous city.

Among the souvenirs I found later that week was a football-sized replica of the famous Kamakura Buddha. It was this replica, a most noble and serene likeness of a most noble and serene human being, that I'd left in brother Michael's care when I went off to college in West Virginia, where we were born and where our grandparents still lived.

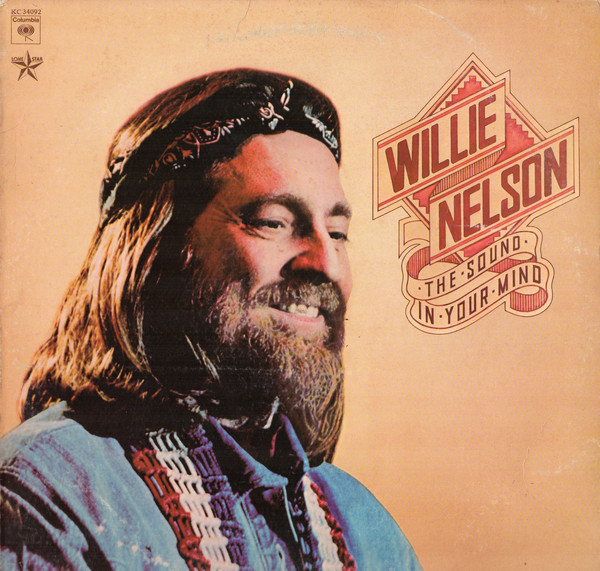

Returning now after my first year of college, I'd found the Buddha at the center of my brother's humble home in sitting meditation on a beautiful batik cloth from India, a few fresh flowers laid out before him with a small bowl of fresh fruit, an unopened can of Billy Carter's "Billy Beer" and, as backdrop to it all, the cover of a Willie Nelson album called "The Sound In Your Mind."

Now for those who have lived under a rock and never got the teachings of the Buddha, I'll explain that there's a long tradition in zen, especially, essentially demanding that we not take the pursuit of enlightenment too seriously.

A fairly famous zen koan, or parable

A monk asked Unmon, "What is Buddha?"

Unmon answered, "A dung-wiping stick."

So naturally, I got it. The sincerity, the humor. All of it.

"That right there is a beautiful thing," I said, sounding a little more like a hillbilly than a Guam haole.

"Yep," he said, and stood beside me in silent agreement.

"Willie, Billy and Buddha," he whispered reverently.